10 of America's Hidden Battlefields

The armed history of the United States can be found in some unexpected places.

There are scores of battles in American history, large and small, that unfolded in unlikely places that even locals may not know about. A savvy visitor can catch a glimpse of this past if they are armed with the right knowledge. This Memorial Day, take a moment to reflect on some of the forgotten battles in this nation’s history.

Battleground Connecticut: The Mystic Massacre, 1636

Location: Along the Mystic River in Connecticut

The Pequot and Mohegan tribes were not always sworn enemies. But linguists and historians agree that a schism occurred in the early 1600s, and it was a violent one. By the time Dutch and English arrived and engaged both sides in trade, the feud had become a grudge. The fur trade added an extra incentive to fight.

In August 1635 a hurricane blew through the region, putting extra stress on everyone living in Connecticut. (Hat tip to the work of historian Katherine Grandjean for this insight.) The fatal looting of an English ship the next year sparked a larger conflict that would change the region forever. England's Massachusetts Bay Colony set about knocking out the Pequots, and the Mohegans were eager to participate. The English invaded Block Island, while Pequots raided English villages.

By 1636 the English and their tribal allies readied a knockout blow — the destruction of a fortified village in what is now the town of Mystic. About 500 men surrounded the fort as 20 snuck inside and started fires on either end. The flames spread quickly, trapping men, women and children inside. Those who came out were attacked.

One of the English leaders, John Underhill, wrote about the event: “The Fort blazed most terribly, and burnt all in the space of halfe an houre; many couragious fellowes were unwilling to come out, and fought most desperately through the palisades, so as they were scorched and burnt…there were about foure hundred soules in this Fort, and not above five of them escaped out of our hands.”

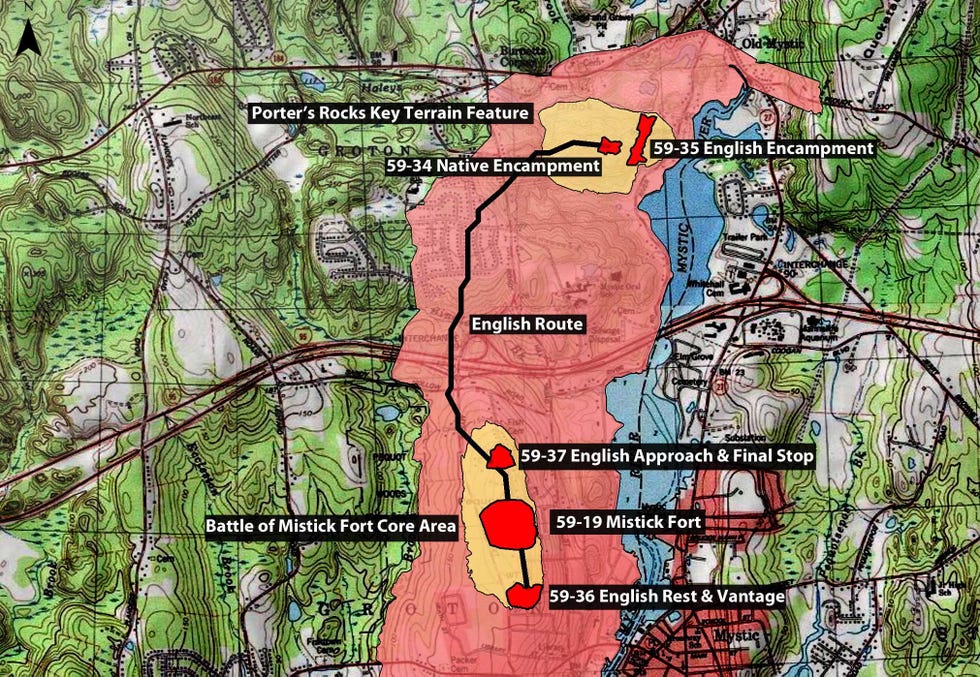

Where to Catch a Glimpse: There’s an active effort to survey and collect artifacts from the Pequots, and they are finding more evidence of the scope of the Native American participation in the campaign. The research produced a map of the key movements in 1936 overlaid on the modern landscape, as seen above. But to get a sense of this long-gone age, find any quiet spot on the Mystic River and imagine the land before industrialization scarred it, when cultures met and clashed in battles that would define the world that followed.

Picture-Perfect Incompetence: Battle of Carillon, 1758

Location: Ticonderoga, NY

Military history is filled with bitter irony. The story of the battle of Carillon certainly qualifies, with deadly mistakes and blundering leading to the creation of a reputation of an “impregnable” fort that didn’t even see the fighting.

The French and Indian War was just one front of a global war, the “Seven Year’s War.” In 1758 the French were facing a superior force on the border between Vermont and New York, where they were building a fort to protect the vital waterways there. Fort Carillon, as it was called, did not impress General Louis-Joseph de Moncalm when he arrived there. He knew there were 18,000 British troops nearby, ready to attack. His forces numbered about 3,600. He saw too many ways that the British could beat and starve his troops into submission if they holed up inside the fort, so he decided to fight the British as they approached. He chose a nearby rise and his troops dug in.

Gen. James Abercrombie, the British commander, ordered an attack on the position. It failed miserably, with French cannon and gunfire cutting down soldiers “like grass,” according to one battlefield communication. The key problem: Abercrombie never paused to use his artillery to reduce the defenses before ordering more waves of attacks. It took all day before he gave up, leaving 1,000 dead and 1,500 wounded. The French lost about 100 troops, with five times that many wounded.

Where to Catch a Glimpse: The British eventually took possession of Fort Carillon, after it had been abandoned a year later. It was renamed Fort Ticonderoga, and it remains one of the best-preserved forts of the era. It enjoyed a fearsome reputation during the rest of the war and the subsequent Revolutionary War. Taking it was supposed to be folly, based on the way the outnumbered French beat the British. The truth is, no major battle was ever fought nearby and the fort’s defenses were never tested.

Fort Ticonderoga is still worth visiting, though. The military engineering is insightful and the on-site demonstrations can transport you back in time. On your way to the fort along Route 74, stare out the passenger’s side window at the site of the real battle—where the slaughter of thousands took place.

Washington’s Worst Morning: The Battle for New York City, 1776

Location: Brooklyn, NY

On August 27, 1776 George Washington was having a bad morning. He had just realized the British duped him with a feint on Long Island as they invaded Brooklyn. Their goal was simple: drive the Continental Army from New York City (and destroy it while they were at it). Washington ordered troops moved from Brooklyn to Manhattan, but the day kept getting worse as the surging British flanked his positions in Brooklyn. He needed to get his rebel force out of New York in a fighting retreat across the Gowanus Creek. (That’s now a canal with the same name.)

Someone had to buy time for the troops. That job fell to a couple hundred troops from Maryland. Typically called the Maryland 400, they probably numbered fewer than 300 in truth. The British set up a defensive line near a stone farmhouse called the Vechte-Cortelyou House. That’s where the Maryland troops made their reckless charge, facing 2,000 British and their cannons. They charged several times, and the British surrounded them. Their last charge broke through the lines and enabled them to surrender to Hessian (i.e. German) mercenaries instead of the hated British. Fewer than a dozen survived and evaded capture.

Where to Catch a Glimpse: This was one part of a massive battle, the biggest of the Revolutionary War. As such, action is spread across wide swatches of New York City. This small drama can be captured at the rebuilt Old Stone House, which is better known for its ghost stories instead of its role in history. The house doesn’t give a great insight into the battlefield, unless you take into account where the Gowanus Canal is, where their comrades were retreating. Another good spot, however, is the intersection of Court Street and Atlantic Avenue. (There's a Trader Joe's there now. Times change.)

This rise, called Cobble Hill (and the namesake of the neighborhood), is where Washington himself watched the action at the stone house. This is where is reported to have said, “Good God, what brave fellows I must this day lose."

The Pirates Lose a Port: Destruction of Barataria Bay pirate colony, 1814

Location: New Orleans, LA

Some legends get more interesting the more you hear about them. Jean Lafitte earns his legendary status, as a smuggler, local business leader, and unlikely battlefield hero. His biggest moment occurred in 1814 when future President Andrew Jackson cut a deal with him to help defend New Orleans from the British.

The forgotten part of the story comes before that happened, with a U.S. attack on a pirate colony that supplied Lafitte with his contraband. It was located on an island in Barataria Bay, south of New Orleans. The residents, a fluctuating population that could grow to 1,000, called themselves Baratarians. It was a complete port, with warehouses, taverns, and facilities to outfit ships flying under the dubious flag of the Republic of Cartagena. Jean Lafitte stayed here, helping ships prepare to raid the seaways and arranging small craft to smuggle the good into New Orleans. There, his brother and other confederates would store and auction the loot.

The U.S., facing some bad times in the against the British (the War of 1812) was afraid that Lafitte would cut a deal with their enemies and help the British take New Orleans. Lafitte has offered his services to the United States, and most historians cite his very real patriotism, but the fear and loathing for the pirate lingered. So in September, a U.S. Navy flotilla headed for Barataria.

The USS Carolina and six gunboats squared off against ten pirate ships that formed a battle line across the bay. The battle was not much of one; the pirates seemed to be buying for time. This was likely by design, as Lafitte wanted room to negotiate with authorities later and a pitched battle would hardly help that cause. After the pirates fled, the U.S. Navy moved in, destroying the facilities and seizing a half a million in contraband on top of the ships that the pirates didn’t torch.

Lafitte and his pirates escaped en masse, and soon cut their famous deal with Jackson to supply cannon and men for the looming battle against the British. This battle would be fought after the conflict was officially over, but before they heard about the cessation. The Baratarians influenced the battle against the British disproportionate to their small numbers because of their experience with cannons.

Where to Catch a Glimpse: Don’t be fooled! The Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve is nice, but it’s located way too far north to be close to the pirate colony’s location. To get to the real spot, take Route 1 all the way to the end of Grand Island. One of the islands you can spy from the park there could double for the pirate colony.

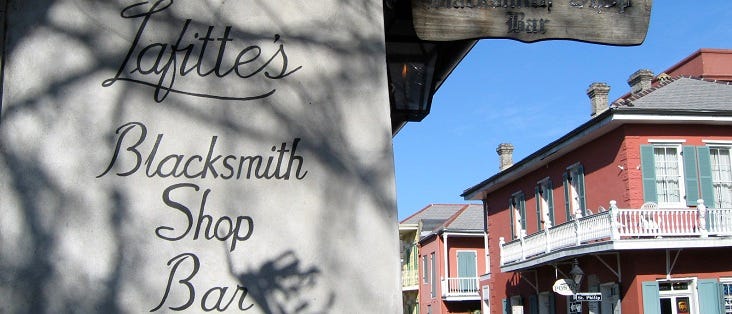

For those who don’t want to leave New Orleans—which is understandable—you can get the feel for the era by knocking back some drinks at Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop. This is one of the oldest active taverns in the nation and is certainly one of the city’s oldest buildings. Documentation is thin, but it’s strongly believed to be one of the pirate’s many front operations where he stored contraband. (His brother and business partner was a blacksmith, and any smuggling business relied on horseshoes as much as small boats and large ships.) You'll find it in the French Quarter at 941 Bourbon Street.

Bloodiest Ground in Texas: Battle of Medina, 1813

Location: Somewhere in Atascosa County, TX

Ask anyone to name the bloodiest battle fought in what’s now Texas and most would say the siege of the Alamo. Texans, sensing a trick, would guess the battles of Jacinto or Goliad. But historians would point to a forgotten, savage battle fought 20 miles outside of what is now downtown San Antonio: the Battle of Medina, fought by insurgents seeking Mexican independence from Spain.

Mexico’s independence from European powers was not quick, easy, or pretty. Efforts to throw off foreign powers had been a dream of locals ( and ambitious Americans) since the early 1800s, when Napoleonic wars in Europe disrupted trade in the colonies. The Texas Historical Association calls the War of Mexican Independence “in reality a series of revolts that grew out of the increasing political turmoil both in Spain and Mexico at the beginning of the nineteenth century.”

One of these revolts involved Tejano, Native American, and American volunteers, who in 1813 declared a free state under a plain green flag. The leaders called their freedom fighters the Republican Army of the North. The rebels captured Nacogdoches, Trinidad de Salcedo, La Bahía, and San Antonio. They had about 1,400 soldiers, under the command of Gen. José Álvarez de Toledo y Dubois, who recently deposed the first leader of the group. They were the first to claim Texas as an independent political entity—and it cost them.

The Spanish crown assembled a force to counter them, with Gen. Joaquín de Arredondo leading 1,800 men toward San Antonio from Laredo. The rebels marched to meet them, with both sides knowing they would collide south of San Antonio. Toledo wanted to lure the royalists into an ambush, but his troops were spotted and chased the Spanish.

The rebels wound up facing a fortified defensive position in an oak forest. A four-hour battle followed, and the attacking rebels were routed. The Spanish massacred those fleeing and those who surrendered. One of the underlings involved in this merciless activity was Antonio Lopez de Santa Ana, who would command the forces many years later at the Alamo, where prisoners were likewise executed. (Massacres tend to beget massacres and Texans showed little mercy at San Jacinto.)

It took until 1821 for the Spanish to sign a treaty granting Mexico independence. Texas gained independence from Mexico in 1836. Amid all the bloodshed and turmoil, the Battle of Medina has been largely forgotten, and its location lost.

Where to Catch a Glimpse: The best historians can do is pinpoint the Medina battlefield somewhere in the northern Atascosa County, along old Pleasanton Road (near the intersection of U.S. Highway 281 and County Road 1604.) After that, people just don’t know for sure. “So disastrous was la batalla del encinal de Medina that its battlefield has become lost, its Green Flag has remained largely unrecognized, and its participants have been generally unknown, unhonored, and unsung,” says the Texas State Historical Association, which has a marker along 281 admitting it doesn’t know the actual location. To get the spirit, drive around the backroads and look for oak groves.

The Battle of the Hemp Bales: First Battle of Lexington, 1861

Location: Lexington, MO

One of the frustrating things about earlier epochs of warfare is commanders' tendency to line up brave men up and send them headlong into gunfire. This lasted much longer than it should have, well into World War I when machine guns betrayed this this tactic as clearly flawed. (Although the human wave attacks by Russian troops in World War II and Chinese forces in the Korean War had a certain bloody effectiveness.)

The point is, get some cover! You’ll live longer. And if there’s no cover available, bring some with you. Soldiers have known this longer than their commanders.

Such is the lesson of the First Battle of Lexington, a Civil War battle that helped the Confederacy keep control over Missouri River Valley. The state did not secede but the slave-owning inhabitants leaned toward supporting the rebel cause — slaves made up nearly 32 percent of the population. The Missouri State Guard formed to fight the Union and federal forces came in to bring them to heel. They soon found themselves hemmed in by rebels in the area surrounding their headquarters.

During the fighting, troops on both sides used bales of hemp to protect themselves from enemy fire. This was a siege, and the rebels knew they’d have to attack defenses and take heavy losses. But soldiers of Brigadier General Thomas A. Harris’ 2nd Division had an idea. They soaked the bales in a river overnight to make them fire resistant and lined them up in front of the union defenses. The rebels rolled the rectangular bales up the slope, hiding behind the bales as the Union troops blazed away. The tactic worked and the exhausted Union troops surrendered just before the Confederates made a final charge.

Where to Catch a Glimpse: The state operates the Battle of Lexington State Historic Site and there’s an easy path along the Missouri River where you can see the incline the Confederates climbed behind their improvised cover. But the most interesting artifact is an errant cannonball lodged in the column of the Lexington Courthouse. The cannonball has not actually been there the whole time – an old man in 1920 donated it to the county and signed an affidavit stating he collected the cannonball after it fell out of its hole. County officials screwed it into place with iron rods, where it remains.

The Californios Make a Stand: Battle of San Pasqual, 1846

Location: San Diego, CA

Colonel Stephen Kearny thought his mission was done. He'd been ordered by President James K. Polk to take California from Mexico (who declined to sell it). After a fairly easy seizure of San Diego, Kearny sent most of his command to Sante Fe, thinking the war was over and the U.S. victorious. Soon, he got word that Californios were ready to fight.

Landowners from Los Angeles and San Diego rallied where the Mexican government failed. Led by Andrés Pico and his brother, Pío Pico, a group called the Californios headed for the San Pasqual Valley (now inside San Diego city limits.) When American scouts neared the Californio camped in a village, a barking dog altered them to their presence. Kearny decided to attack, and his men (defying his orders to go slowly) charged in on horseback. A hail of gunfire drove them back, and the Californio cavalry soon counterattacked. The horsemen were armed with lances while the Americans had sabers. That extra range ended with 20 American deaths to only one Californio.

It was to be the Californios high water mark. After local and U.S. government reinforcements arrived, the Mexican militia negotiated a surrender. California now belonged to America.

Where to Catch a Glimpse: The good thing about skirmishes, as opposed to large battles, is that the reenactments are easier to get right. With such a small fight, Battle Day is a good chance to remember this slice of California history. The annual reenactment takes place on the Sunday closest to December 6 at the San Pasqual Battlefield State Park. For a more visceral experience, park at the lot away from the monument and take the winding, mile-long foot trail to the monument at the western edge of the park.

The Gulf is Burning: The Battle of Fort Blakeley, 1865

Location: Mobile, AL

The Gulf of Mexico is a forgotten battleground of the Civil War. The Union strategy depended on strangling the Confederacy, and that meant controlling the rivers and ports. Mobile, Alabama was a crucial target and taking the forts that protected the city was a longstanding priority. Even though the U.S. Navy blockaded the city since summer 1864, it took the entire war to win the city.

Fort Blakeley was one place that needed to be taken in order for the city to surrender. It wasn’t easy, despite the numbers. Confederate Brig. Gen. St. John Liddell commanded 3,500 men while the Union had 16,000 troops moving in on them. Among the ranks were 5000 black troops, the largest concentration of the “United States Colored Troops” to fight a battle in the war.

The Union followed the siege textbook: dig trenches to get close enough to the defenses to launch an attack. Confederate artillery and warships did their best to disrupt them with cannon fire. On April 9 the final assault began, with onrushing Union troops tripping landmines and showered with rifle and cannon fire. Late in the afternoon, the federal troops breached the defenses and the Confederates surrendered after a brief hand-to-hand combat. The Union days later occupied Mobile. The fight is overshadowed by the fact that on April 9 Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered his army at Appomattox.

Where to Catch a Glimpse: The Battle of Mobile Bay takes most of the attention, and rightfully so from a historic and tourism standpoint. (It even has it’s own catch phrase, “Damn the torpedoes!”) The Old Spanish Fort, bombarded and besieged by the Union, is an amazing place to explore. Don’t skip it; it also has World War II vintage coastal defense batteries, which are amazing. But a visit to the Historic Blakeley State Park is a great companion. Tours bring visitors to the earthworks that formed both Confederate and Union lines. The trenches, artillery positions and rifle pits feel like World War I rather than a stereotypical set-piece Civil War battle. They are well preserved and not often visited. Since this was the last great battle of the Civil War, the place has added significance and emotional impact.

The Attack of the Fire Balloons: Japanese lighter-than air bombing campaign, 1945

Location: Bly, OR

The war seemed pretty far away from Bly, Oregon on May 5, 1945. It was a nice day so, Reverend Archie Mitchell took his Sunday school students on a picnic. The children and his wife Elsie walked ahead, and spotted something on the ground. They approached with curiosity when the object exploded. Sherman Shoemaker, Edward Engen, Jay Gifford, Joan Patzke, and Dick Patzke, all between 11 to 14 years old, were killed, along with Mitchell’s wife.

During WWII, the Japanese eagerly sought some way to reach across the Pacific and cause damage to the United States. They built hundreds of balloons carrying four incendiaries and one 30-pound high-explosive bomb in each. In November 1944, Japan started releasing their balloon bombs into the Pacific jet stream.

The idea was to cause industrial damage, forest fires, and most of all, panic. The damage was inconsequential and U.S. censors kept any panic away. After the Sunday school incident, the censors issued warnings to stay away from strange objects.

Where to Catch A Glimpse: The Mitchell Memorial is easy to find, 13 miles northwest of Bly. It’s haunting — Elsie Mitchell was pregnant and other young lives were lost needlessly — but also surprisingly visceral. A nearby Ponderosa Pine still bears the scars of the blast. Historians believe there are more undiscovered balloon bombs out there; one was discovered in 2014.

Florida’s Forgotten U-Boat Massacres: German Submarine Campaign, 1942

Location: Miami, FL

At 10pm a German U-boat Capt. Reinhard Hardegen watched the lights twinkle on the shoreline of Jacksonville, Florida. His job was to sink oil tankers and other ships, but also to remind the United States of Germany’s lethal reach.

The 445-ft-long SS Gulfamerica carried 100,000 of oil and was sliding past Jacksonville just 5 miles from the shore. The U-boat, numbered 123, saw the shi- plainly against the lights of the resort on shore. Hardegen ordered a torpedo fired that blasted the starboard side and caused a fire. The submarine fired 20 cannon shots into the ailing ship, aiming for communications antenna and a anti-aircraft gun. Then he slid away, to strike again later. Nineteen of the 48 onboard were killed.

This was just one of dozens of close-to-shore sinkings in World War II. Outside New Orleans, Miami and New England the horizon line would light up and oil slicks would wash onto shore. The censors downplayed the terror but the fact remained that until the U.S. created airplanes and anti-submarine ships — and crews, many times volunteer to man them — the German navy could strike with impunity.

For a great, thorough primer on the war for Florida, see this document.

Where to Catch a Glimpse: Walk Miami Beach and imagine the volunteers who biked up and down its length, seeking to spot submarines. Or go to Jacksonville and imagine the night in 1942 when the Gulfamerica went down. Go there at 10pm or so and imagine the sky suddenly igniting. But really, anytime you star out at the Gulf of Mexico or anywhere along the Atlantic seaboard and you see an oil tanker, imagine a hidden metal shark circling it, ready to blast it into pieces.

Joe Pappalardo is a contributing writer at Popular Mechanics and author of the new book, Spaceport Earth: The Reinvention of Spaceflight.

The ‘Space Laser’ Wars Have Begun

The World’s First ‘Fighter Drones’ Are Coming

We’re Already Fighting the World’s First AI War

Ex-Navy Official: UFOs Are Hiding in Our Oceans