Chasing Black Caesar, Southern Florida’s Notorious Pirate

Was the terror of Biscayne Bay a man who escaped slavery, an African chieftain, or a marketing ploy that went viral?

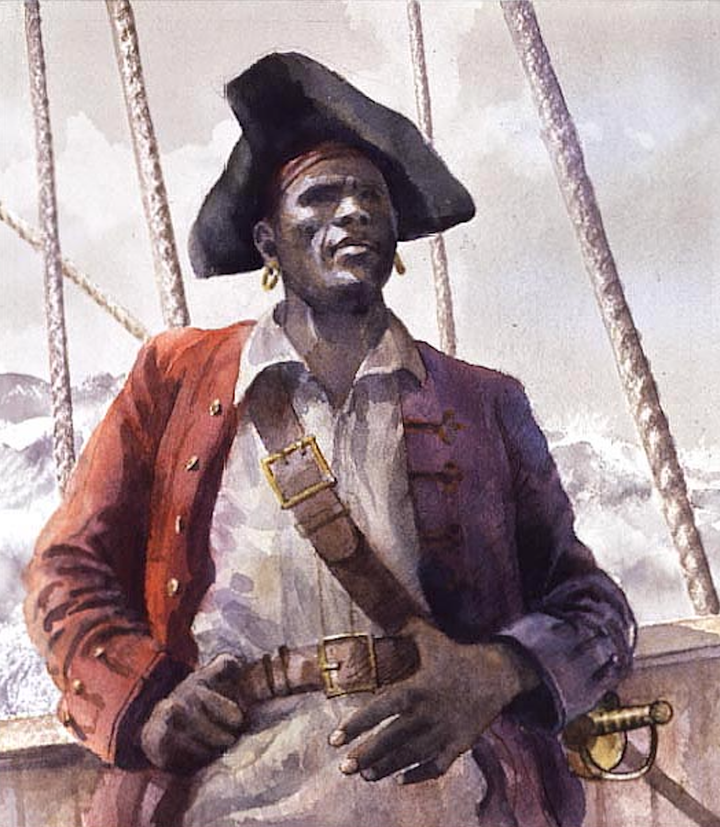

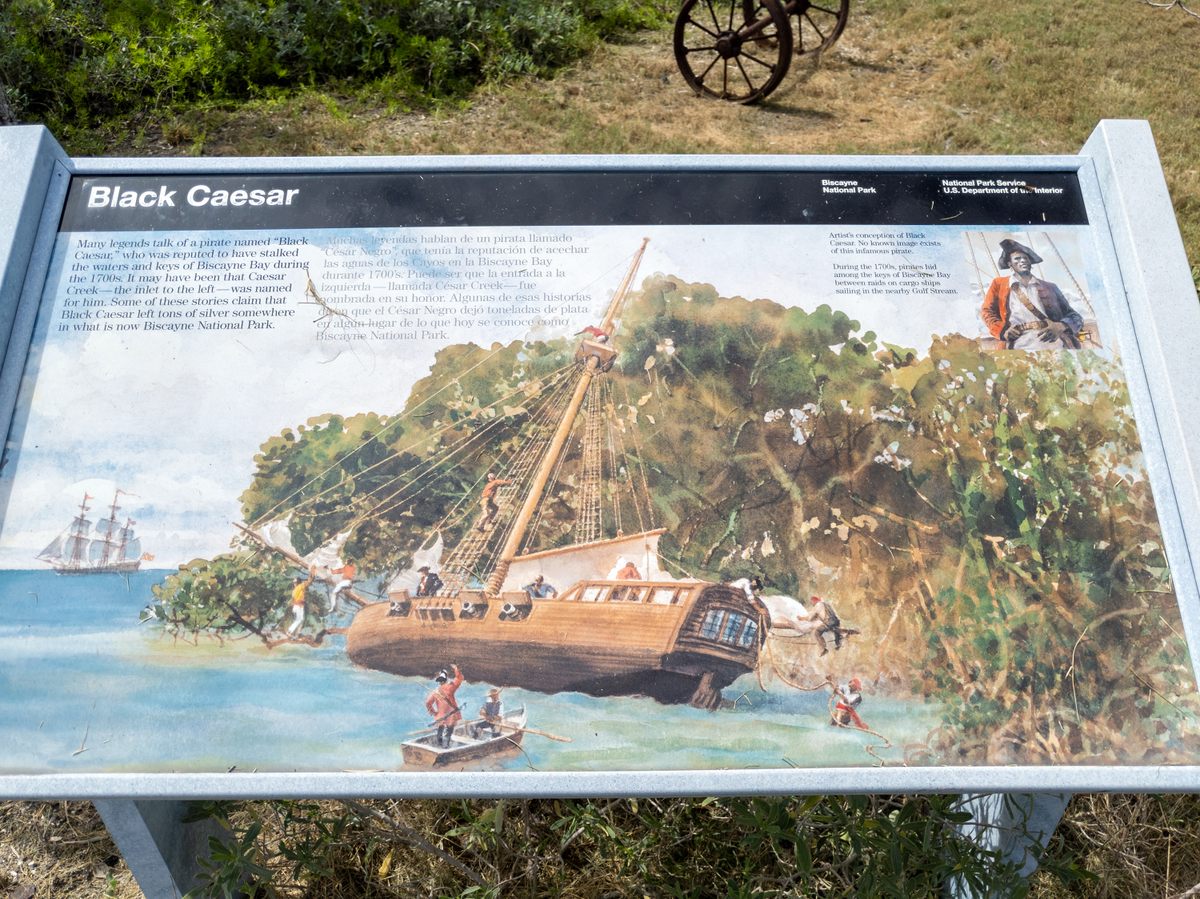

The first time maritime archaeologist Joshua Marano stood at the mouth of Caesar Creek, something smelled fishy. Overlooking a snaking waterway of tangled emerald mangroves and silver-flanked snapper stood a lone interpretive sign. It featured a drawing of a courageous Black man wearing a tricornered hat and looking wistfully toward the horizon.

“Many legends talk of a pirate named ‘Black Caesar,’ who was reputed to have stalked the water and keys of Biscayne Bay during the 1700s,” the sign states. “Some of these stories claim that Black Caesar left tons of silver somewhere in what is now Biscayne National Park.”

Marano had heard about the pirate Black Caesar: an African chieftain shanghai’d into pirate life, or perhaps an escaped slave. Either way, the stories claimed that he plied the waters of southeastern Florida’s Biscayne Bay. He would lie in wait by careening his ship on its side, secured with a rope, to conceal its mast below the mangroves of Caesar Creek. The rope looped through an iron ring fixed in a limestone boulder now known as Caesar’s Rock. When a vulnerable vessel came into view, he would chop the rope, set sail, and begin pursuit.

“As a mariner, I go to that creek and look at the rock [and] it just makes no sense,” says Marano. The channel is narrow, with a high current and plenty of rocks. The open ocean is also three miles from the creek, requiring careful navigation through treacherous reefs just to reach it. Black Caesar’s alleged strategy, Marano says, “is the dumbest idea I could think of.”

As the park’s maritime archaeologist, Marano looked for hard evidence of Black Caesar in Biscayne. He found none, which started him on a new quest.

“I’m working diligently to have that sign removed,” says Marano. “I’m not a cranky old archaeologist, but there’s no archaeological evidence that there was ever a pirate in this location and it does have detrimental impacts to make that kind of claim.” Detrimental may be an understatement: Modern-day treasure hunters have actually blown holes in the islands searching for Caesar’s treasure.

Beyond the boundaries of what’s now the national park, there are tales of other Black Caesars: One, reputed to be part of Blackbeard’s crew, was allegedly captured and hanged in 1718 in North Carolina. The other terrorized the Gulf Coast of Florida in the 1800s, alongside the infamous pirate José Gaspar.

The Blackbeard Black Caesar story has been debunked by pirate historian Robert Jacob, who uncovered that Caesar was not a pirate, but an enslaved man visiting Blackbeard’s camp with his enslaver who, says Jacob, “saw the lights and heard the party noise and came over to have some rum with Blackbeard and his crew.”

The Blackbeard connection dates back to a 1724 publication, The General History of Pirates, by Charles Johnson. “About 90 percent of what Charles Johnson writes is incorrect. He made up lots of stuff,” says Jacob, adding that, according to the trial records, Caesar was actually acquitted.

As for the Gulf Coast Black Caesar, some versions say he was born Henri Arnaut, a Haitian man who escaped slavery by capturing a small Spanish ship in 1804. He changed his name to Caesar, and, after pillaging and burying his loot somewhere in Biscayne, made his way to the Fort Myers area, where he joined forces with Gaspar. There is, however, no historical evidence of this Black Caesar, Gaspar, or the $30 million they supposedly buried in Boca Grande.

“In fact, we know the guy who invented José Gaspar,” says Jacob. The Gasparilla Inn on Boca Grande hired a writer named Pat LeMoyne in the early 20th century to drum up business with some colorful marketing materials that featured, says Jacob, “the pirate Gaspar and all kinds of horrible pirate tales of atrocities, [with] Black Caesar as one of his partners.”

During this era, over-the-top pirate tales happened to be popular, and fishing guides for Florida’s burgeoning sport fishing industry soon discovered that spinning the best rip-roaring pirate yarns won them the wealthiest clients and biggest tips. Some even started selling fake treasure maps.

“This is where all of the buried treasure stories came from,” says Jacob. Pirate legends were also good for the owner of the Gasparilla Inn, who was developing the island of Boca Grande. “Can you think of a better real estate gimmick than to say there’s $30 million buried here somewhere… Maybe it’ll be on the plot of land you buy.”

Tales of Black Caesar living in Biscayne started soon after, fueled by the 1922 novel Black Caesar’s Clan and other works.

“They’re fun stories,” says longtime Biscayne park ranger Gary Bremen, who has told a few Black Caesar tales to visitors. “People like pirates. They have this romanticized notion, but these were criminals. … So I did share some of those stories, but with the caveat that there’s a lot of baloney.”

While Biscayne’s Black Caesar does appear to be baloney, it may have persisted because of the bay’s deep-rooted Black history. In 1827, a slave ship sank on a nearby reef, killing dozens of people. The bay was also part of the Saltwater Railroad—a maritime version of the Underground Railroad—and the visitor center sits atop what was once a segregated beach. And, for nearly a century, the Joneses, a Black family, lived on Porgy Key, an island along Caesar Creek and just a few hundred feet from Caesar’s Rock.

Biscayne Bay native John Nordt was friends with the late Sir Lancelot Jones, who lived on the creek from 1898 to 1992, and once asked him about the iron ring on Caesar’s Rock. “He said he never saw a ring,” says Nordt. “He said it was a story made up by a Miami Herald writer.”

As for the millions Caesar allegedly buried somewhere in the bay, Jones did share a theory with Nordt about that, recalling that men digging a cistern on a nearby island apparently found human remains. The men “got spooked and left,” says Nordt, adding that Jones recalls one of them turning up months later with an impressive 80-foot schooner. “[Jones] figured he must have found pirate gold.”

Gold or no gold, Marano’s quest to get the interpretive Black Caesar sign removed is moving slowly through the bureaucratic process.

Jacob, for his part, would like to see the sign remain. “The legend of Black Caesar is still history,” he says. “It’s just a different history than the one on the sign. The story is the story, not the man.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook