50 States of Wonder

6 Fascinating Medical Marvels in Pennsylvania

In the 1700s and 1800s, Philadelphia was the center of medical scholarship in the United States. The city not only attracted the brightest minds, but also the most curious cases and characters. From the oldest quarantine facility in the country to a museum that memorializes a traveling dental circus, here are six places to marvel at the trials, errors, and triumphs of medical history in Pennsylvania.

1. Lazaretto Quarantine Station

About 11 miles south of Philadelphia along the Delaware River lies the oldest quarantine station in the United States. Six years after a yellow fever epidemic swept through the city in 1793, the newly formed board of health set up Lazaretto Quarantine Station to inspect every person and piece of cargo that was heading to Philadelphia. Sick passengers were detained at the site’s hospital. Those who improved left; those who didn’t ended up in Lazaretto’s burial grounds.

After closing in 1895, the site served as a country club and a seaplane airbase before falling into disrepair. Last year, the local government finished renovating several of the buildings and opened the grounds to tours. Although they have suspended visits due to COVID-19, you can still listen to the online audio tour—which guides you around the site with narration from primary-source accounts—as you keep your distance during our modern pandemic. (Read more.)

99 Wanamaker Ave, Essington, PA 19029

2. America's Oldest Operating Theater

On any given day at Pennsylvania Hospital, surgeries are performed around the clock, with skilled anesthesiologists assisting the process. This wasn’t always the case. If you were in the audience of the hospital’s operating theater in the years just after it opened, in 1804, you’d watch surgeries performed only on sunny days (for better visibility, as there was no electricity). At the time, “anesthesia” came in the form of rum, laudanum, or a whack on the head with a mallet. The latter was administered with enough force “to render the patient unconscious and hopefully not dead.”

Though no one has performed surgery inside it since 1868, the operating theater—the oldest in the United States—has been preserved. Its seats may no longer be filled with rowdy medical students, but it still attracts an audience of visitors who come to glimpse a bygone era of medical history. (Read more.)

800 Spruce St, Philadelphia, PA 19107

3. Science History Institute

With a strong focus on chemistry, the Science History Institute traces the evolution of medicine through art, artifacts, and rare books on alchemy and modern pharmacology. Its massive library houses 16th-century tomes containing recipes for the philosopher’s stone (which could allegedly turn ordinary metals into precious ones such as silver and gold). The rest of the museum boasts an impressive array of historic paintings that depict the changing roles of healers over time, and its shelves showcase artifacts—including bloodletting bowls and earthenware leech jars—that demonstrate just how much medicine has changed. The museum is currently closed to the public, but you can “visit” digital versions of some exhibits on their website. (Read more.)

315 Chestnut St, Philadelphia, PA 19106

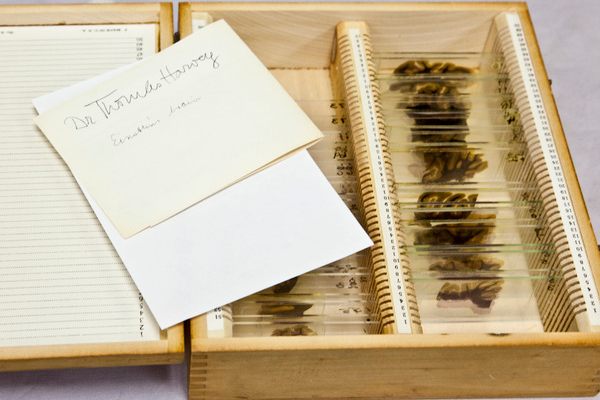

4. Mütter Museum

In 1858, Dr. Thomas Dent Mütter donated his collection of 1,700 medical specimens and objects to the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. The result was the beginning of what has come to be known as the Mütter Museum, a medical wunderkammer packed with skulls, specimens, and wax models of anatomical anomalies. Today, the collection has grown to 25,000 items, including Grover Cleveland’s jaw tumor; the shared liver of Chang and Eng Bunker, famous conjoined twins of the 19th century; and the “soap lady,” an unidentified corpse coated in a unique fatty substance called adipocere. Try to spot signs of genius in the displayed slices of Albert Einstein’s brain and be sure to peruse the wall of skulls that Dr. Joseph Hyrtl once used to debunk phrenology. (Read more.)

19 S 22nd St, Philadelphia, PA 19103

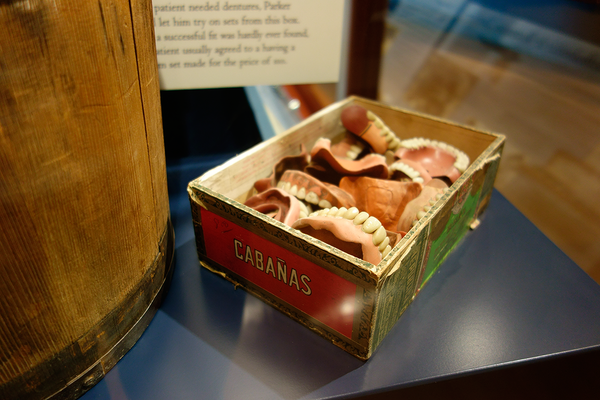

5. Weaver Historical Dental Museum

From vintage dentures to a replica of a 19th-century dentist’s office, toothy treasures abound inside the Weaver Historical Dental Museum at Temple University. But the most striking item in the collection is a wooden bucket filled with old, dirty teeth. Each was extracted by Edgar R. R. Parker, one of the dental school’s most infamous alumni. After graduating in 1892, “Painless Parker” combined dentistry with showmanship, traveling around the country in a horse-drawn wagon with a backup band who played (and conveniently drowned out any screams) as he “painlessly” extracted townspeople’s teeth for 50 cents each.

Parker’s methods were crass and often not at all painless, leading the American Dental Association to call him “a menace to the dignity of the profession.” Still, he brought affordable dentistry to the masses at a time when access was limited. A plaque at the museum acknowledges Parker’s impact: “Much of what he championed—patient advocacy, increased access to dental care and advertising—has come to pass in the U.S.” (Read more.)

3201 N Broad St, 3rd floor, Philadelphia, PA 19140

6. The Nervous System of Harriet Cole

An unusual greeter stares at passersby in the Drexel University School of Medicine’s student center. The human-shaped assembly of tendrils and two eyeballs is the completely extracted and reassembled nervous system of one Harriet Cole. Once a cleaning woman at Hahnemann, founded as a homeopathic medical school, Cole is said to have donated her body to its anatomy department in the 1880s.

In 1888, Dr. Rufus Weaver spent five months unearthing and extracting Cole’s nervous system, coating the nerves in white, lead-based paint and shellacking them for display. In addition to bringing Cole’s nervous system into the classroom for educational purposes, Weaver also brought it to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, where it earned awards. While you don’t have to wait until the next World’s Fair to see Harriet, you will have to wait until the next event in which Drexel opens the student center to the public. (Read more.)

2900 W Queen Ln, Philadelphia, PA 19129