This mountain town has stayed off many folks’ radars by keeping some of its greatest attractions at or beyond city limits.

Asheville: Off the Beaten Path

With bustling food, music, and brewery scenes, Asheville has plenty of attractions—but stick to the downtown area alone, and you’re missing half the fun, at least. Surrounded by national forests, hideaway mountain towns, quirky arts centers, and more, some of Asheville's best spots lie beyond the downtown area. This itinerary will help you navigate America’s weirdest little mountain town like a local as you scale mountaintops, watch artisans at work, ride century-old trolley cars, and get fake-married at a real-live punk bar. Welcome to Asheville.

1. Fleetwoods

Despite an unsuspecting facade, there’s a lot going on at this West Asheville dive. Fleetwood’s slogan reads “Shop. Drink. Get married,” but even that’s an understatement.

With about a dozen racks of curated vintage clothing and accessories—yes, there’s plenty to shop. With a full bar offering local beers and ciders on tap beside an array of original cocktails—yes, you can drink, too. And with several ordained ministers on staff, you can even be legally wed in their on-site chapel (they also offer “Fake as Hell” wedding ceremonies for those who are slightly less serious about the institution). Couples often allow bar patrons to attend their special day—you may even be asked to serve as a witness.

There’s also the music.

When vows aren’t being exchanged, the “chapel” doubles as an all-ages live music venue for local and regional acts ranging from avant-garage punk to indie to psych-pop. And when there’s no professionals around, Fleetwood’s offers Terraoke—their personal brand of punk karaoke. Oh, and every weekend there’s also Junk-o-Rama, their weekly vintage flea market featuring a handful of local vendors.

Sing your heart out, shop ‘til you drop, or tie the knot—or maybe all three? If it all feels overwhelming, take a load off at the bar.

496 Haywood Rd, Asheville, NC

2. Peace Gardens & Market

In 2003, a West Asheville couple launched the Peace Gardens & Market as a place of healing for a disenfranchised community without many non-commercial meeting places. In the years since, the hillside gardens have grown—much like Fleetwood’s—to evade simple categorization.

The property itself is home to not only a live farm growing rotating seasonal crops for sale at weekend markets, but also an immersive and ever-changing network of murals and found-object art installations. The work explores local and national chapters in Black history, both trials and triumphs, from gun violence and the War on Drugs to advancements in civil rights and episodes from recent Black Lives Matter protests.

This is not to say it’s all heft—there’s also a performance stage, library, fire pit, pizza oven, and several meditation areas strewn throughout the grounds, making it something of a choose-your-own-adventure that’s both informing and engaging. On select weekends, gardening workshops are offered to the public.

Beyond the property, the founders also offer “Hood Tours,” guided walking and driving excursions through Asheville’s historic Black neighborhoods and churches. Check their website for upcoming events and workshops.

47 Bryant St, Asheville, NC

3. River Arts District

In reality, most “arts districts” are residential areas with a handful of consolidated studios and galleries. The River Arts District (R.A.D.) southwest of downtown Asheville, however, is not most arts districts.

Here, on the banks of the French Broad River, over 200 artists are at work across 22 buildings within a one-square-mile radius—a living arts neighborhood that’s as walkable as it is interactive.

The studios and galleries are primarily housed in a network of defunct industrial warehouses, strategically built in the late 1900s along the Norfolk Southern Railroad. By the 1970s, the industry had shuddered, and a downtown “renaissance” displaced many of the days’ artists, making today’s R.A.D. a triumph in both artistic resilience and urban renewal.

Color-coded maps help visitors stroll the breadth of the district by both medium and artist, making it easy to view artists at work, purchase pieces from the makers themselves, and even participate in workshops led by professional craftsmen and women.

While the district’s been largely impervious to over-development, it has made room for a handful of cafes, breweries, and restaurants (one of which became a favorite of then-president Obama on a 2008 visit).

3 River Arts Pl, Asheville, NC

4. Montford Park Players

It’s estimated that only fifteen theater groups in the world have performed Shakespeare’s entire canon—every comedy, every history, every tragedy. Sure enough, one of them is tucked in an urban park west of downtown Asheville. With a hand-built, Elizabethan era-style stage framed in a thicket of dense evergreens, it would feel like a step back in time were it not for the professional-grade lighting system.

The Montford Park Players put on free shows from spring to fall on a multi-platformed outdoor stage in Asheville’s historic Montford neighborhood. The stage’s placement at the bottom of a gently sloping hillside grants unobstructed views for all attendees while also amplifying onstage dialogue. Much like in the Globe Theater of old, the Players perform without microphones, though that’s roughly where adherence to tradition ends.

Far from your run-of-the-mill “Shakespeare in the Park,” the Players take great liberty with the Bard’s works, and to great acclaim. They reimagine Midsummer Night’s Dream in an Appalachian setting (complete with mountain accents), Pericles as a travel blogger, and play fast-and-loose with different characters’ genders. Leveraging their unique location, action also either spills off-stage into the audience or on-stage from the surrounding woods.

And of course, while Shakespeare is their calling card, they’re not confined to him either. The Players have performed James and the Giant Peach, the Little Prince, and Living Dead in Denmark—a Shakespearian universe spin-off in which Lady Macbeth, Juliet, and Ophelia are brought back from the dead to wage war against an army of zombies—not technically canon, to be sure.

92 Gay St, Asheville

5. Montford Historic District

Leaving the Montford Park Players’ domain, you may notice the inordinate number of stately mansions perched on beautifully forested, dramatic hillsides, with dignified names like ‘Ambassador,’ Rumbough,’ and ‘Homewood’ engraved into marble panels over heavy wooden doors. Indeed, a majority of the homes in Asheville’s iconic Montford neighborhood are on the National Registry of Historic Places—and for good reason.

With a humidity, temperature, and elevation once thought ideal in treating tuberculosis, Asheville was once the mecca of moneyed TB patients seeking a restorative environment in the early 1900s. Folks from all over the country left behind ostentatious homes and chose to rebuild here in the fresh mountain air during their recuperation.

The result is a smorgasbord of over 600 strikingly handsome mansions connected by wide, tree-lined roads that snake and loop around the hillsides north of downtown. Montford homes boast an array of turn-of-the-century architectural styles including Victorian, Queen Anne, Neoclassical, and more, with features like high-pitched roofs, heavy stone foundations, and palatial wraparound porches making frequent appearances. The neighborhood’s oldest home, the Rankin House, is an 1843 Greek Revival-style building that’s now—like many Montford buildings—a bookable bed & breakfast.

While most private homes are best viewed from a slow cruise or walk around the neighborhood, several homes do open their doors for holiday strolls.

Although the science behind mountain airs’ healing properties is inconclusive, it certainly couldn’t have hurt to live in such a serene locale—with one notable historical exception.

Asheville, NC

6. Highland Hospital

As much as the region’s agreeable climate once attracted wealthy tuberculosis patients to the region, the work of a distinguished psychiatrist named Dr. Robert Carrol once drew the mentally ill among affluent families to a now-infamous facility sitting atop a great hill within the Montford neighborhood: Highland Hospital.

When it opened in 1904, the psychiatric field had just begun shifting away from the grim asylum systems of old, which viewed patients as irremediable and in need of sheltering. Instead, Dr. Carrol’s approach emphasized physical exercise, occupational therapy, and diet as means of helping patients with addiction and “nervous disorders” rejoin society. In time, Highland’s progressive approach came to attract somewhat of a celebrity clientele, including author F. Scott Fitzgerald's wife, Zelda, who lived with schizophrenia.

It’s unclear what exactly started the fire in March of 1948. What’s more clear was the aftermath: nine women—including Zelda—passed away that night. In remembrance of the tragedy, no building was erected on the site of the hospital, which is today a quaint, grassy field. All that remains of Highland’s legacy are ‘Homewood,’ the magnificent stone-built castle-style home where Dr. Carrol lived, and Highland Hall, a Colonial Revival building that served as an administrative center.

Its connection to the hospital is today marked by a plaque near the front door bearing a heartrending quote from one of Zelda’s letters to her husband: “I don’t need anything except hope, which I can’t find by looking forwards or backwards, so I suppose the thing is to shut my eyes.”

75 Zillicoa Street, Asheville, NC

7. Historic Grovewood Village

In the shadow of the iconic Omni Grove Park Inn north of downtown, a century-old complex boasts historic renown all its own.

Historic Grovewood Village was the 1917 birthplace of Biltmore Industries—at one point the largest producer of handwoven wool in the world (and the engine of wealth that would help build what is still today the largest private home in the country—Asheville’s Biltmore Estate.)

While weaving ceased in the 1980s, the multi-faceted complex that visitors can see today (free of charge) pays homage to the area’s legacy of craft and industry.

There’s the Homespun Museum, featuring historic industrial memorabilia (like an antique four-harness loom) as well as a sprawling facility featuring original equipment once dedicated to producing and dying prodigious sums of wool. There’s the Grovewood Gallery, home not only to eight working artist studios (on-site now: flute-maker, ceramicist, glassblower, and more) but a gallery selling works from over 400 American artists in a range of media from woodwork to furniture to watercolor. There’s also the Estes-Winn Antique Car Museum, featuring rare models including a 1957 Cadillac Eldorado (only 400 made) and Asheville’s very own 1922 LaFrance fire truck. For the outdoor-adjacent, a delicate walkway meanders through the Village’s lushly vegetated 11-acre sculpture garden as well.

It’s a charming historical complex with something for everyone that’s worth every penny you don’t have to spend.

111 Grovewood Rd, Asheville, NC

8. Craggy Mountain Line

Many modern Ashevillians may not know this, but at the turn of the 20th century, their city was home to the second-largest trolley system in the country. The folks at the Craggy Mountain Line museum certainly haven't forgotten.

Their outdoor rail museum retains the last trolley line in the region that hasn’t been ripped up or covered in pavement. The Craggy Mountain line was built in 1904 when railroads were highways and day trips with the family meant a ride along one of the city's many trolleys into the surrounding mountains.

Visitors today can relive the outings of old on a roundtrip ride through Elk Mountain on a 1930s trolley car. The scenic alpine rail-trail careens 3.5 miles around the gentle mountainside and along the French Broad River through the city's newest park, the soon-to-be-opened Silver-Line Park.

Back at their “depot,” Craggy Line’s enthusiastic all-volunteer staff acquires and maintains rare historic railroad equipment to its original condition, which includes a former NYC subway system A Train from the 1930s (one of seven left on earth) as well as an Edwards Motorcar Doodlebug from 1926 (one of ten remaining).

111 Woodfin Ave, Asheville, NC

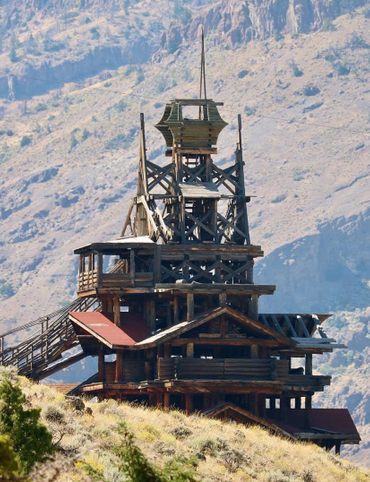

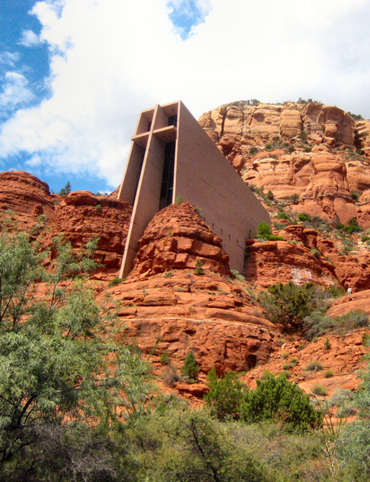

9. Fryingpan Mountain Lookout Tower

The best part of finishing a grueling hike through the unforgiving wilderness is often taking in the panoramic views from the peak of whichever mountain you’ve just summited. A historic lookout tower along the Blue Ridge Parkway outside Asheville, however, grants you all the views with almost none of the hike.

The Fryingpan Mountain Lookout Tower was built by the U.S. Forest Service in 1941 as a means of spotting wildfires around the northern edge of Pisgah National Forest. At 70 feet tall, the tower juts out from the peak of Fryingpan Mountain, itself named by mountain herders—the story goes—for a communal frying pan once hung from a nearby tree. A dizzying 5,340 feet in elevation makes this one of the highest towers of its kind in the state.

Today, the lookout tower is functionally obsolete but certainly hikable. Park in the dirt pull off a half-mile north of Fryingpan Tunnel and follow the gravel road uphill to the tower (a 20–40 minute endeavor). You’ll pass rhododendrons, wildflowers, and—in the late summer months—wild blueberries along the .75 mile incline. Visitors can then scale the narrow staircase to the lookout cabin for sweeping views of Pisgah Forest, Looking Glass Rock, Cold Mountain (of literary fame), and Mt. Pisgah itself.

Note that the nearly century-old tower is stable but certainly past its prime. Those with acrophobia or dogs may prefer to enjoy the views from the base of the tower or at one of the many scenic pull-offs along the Blue Ridge Parkway.

Canton, NC

10. Swannanoa Valley Museum

Even against downtown’s tallest buildings, the majestic peaks that frame metropolitan Asheville are an enduring reminder of the unsung scale of the Appalachian range and North Carolina’s natural beauty. They make this unique mountain town a difficult place to leave—metaphorically, if you’re a present-day traveler—and also get to, if you were, say, a westward settler. The only clean way in from eastern North Carolina was through Swannanoa Valley, winning this highly trafficked corridor enough fascinating stories and characters to warrant its own museum.

The Swannanoa Valley Museum packs an impressive historical punch into a two-story, 1920s brick firehouse located in the heart of charming Black Mountain, NC. The first floor is a rotating annual exhibition (fittingly, the town’s firefighting history at the time of publication), while the second floor tells the human history of this fertile and long-populated valley.

From early Cherokee settlements through the mid-20th century, displays make pit stops at obscure but fascinating community figures of both local and national fame, like Horace Rutherford, who opened a renowned Appalachian juke joint during segregation, and Lilian Exum Clement, the first woman elected to U.S. state legislature—before women even won the right to vote.

The museum has a bit of an active side, as well. They offer a series of guided “Rim Hikes”— hiking or 4x4 excursions that take visitors to historic or abandoned communities dotting the mountains around this storied valley. Check their website for availability.

223 W State St, Black Mountain, NC

11. Montreat Rocky Head Trail

If you found the hike to Fryingpan Tower dull, this trek just north of Black Mountain may offer the challenge you’re after—and then some. In less than a mile, the Rocky Head Trail ascends over 1,000 feet to the peak of Rocky Head (4,019’ elevation), offering arresting views of the valley far, far below.

Plug “Montreat Campground” into your navigating system, and you’ll climb along the banks of a lightly babbling creek through the delightful 700-person forest village of Montreat. If the campground is open, park where available; If it’s offseason, park outside the gate and walk through the campground until you see a bathhouse on your right. A small sign behind the building will point you uphill to the trail (emphasis on ‘uphill’).

If a strenuous hike is not your cup of tea, walk past the bathhouse until you see a sign that reads ‘MICA’—from there, a 5-minute hike will lead you to the site of indeed a former mica mine, unmistakably evidenced by the bits of mica laced into the surrounding soil.

If it’s the Rocky Head Trail for you, expect very little flat ground (in fact, walking sticks are a great help, here). Following orange diamond markers as a guide, you’ll ascend a rugged path through dense rhododendron thickets, then oak groves, passing old water-holding ponds used for electrical generation plants in the early 1900s at about the midpoint. Once you see Fraser Firs and jaw-dropping views over the right side of the trail, you’re nearing the peak. The summit is ringed with trees, but in winter months offers 360° views of the surrounding mountains. Bring your binoculars, and you just may be able to see Asheville from here.

99999 Calvin Trail, Black Mountain, NC

This post is sponsored by Explore Asheville. Click here to discover more.